1995 CHEVROLET TRACKER tires

[x] Cancel search: tiresPage 62 of 354

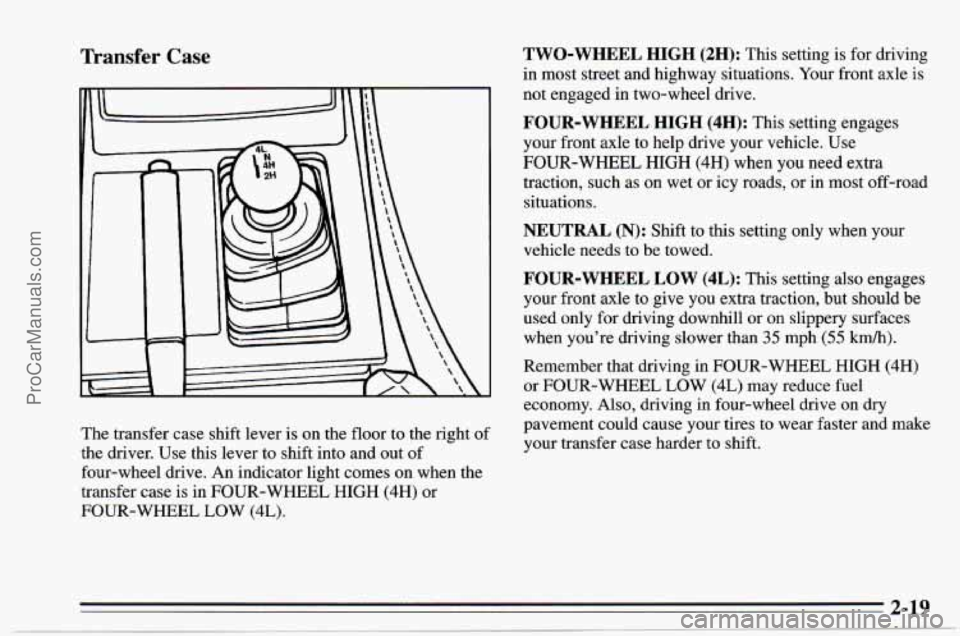

Transfer Case

The transfer case shift lever is on the floor to the right of

the driver. Use this lever to shift into and out of

four-wheel drive. An indicator light comes on when the

transfer case is in FOUR-WHEEL

HIGH (4H) or

FOUR-WHEEL

LOW (4L).

TWO-WHEEL HIGH (2H): This setting is for driving

in most street

and highway situations. Your front axle is

not engaged in two-wheel drive.

FOUR-WHEEL HIGH (4H): This setting engages

your front axle

to help drive your vehicle. Use

FOUR-WHEEL HIGH (4H) when you need extra

traction, such as on wet or icy roads, or in

most off-road

situations.

NEUTRAL (N): Shift to this setting only when your

vehicle needs to be towed.

FOUR-WHEEL LOW (4L): This setting also engages

your front axle to give you extra traction, but should be

used only for driving downhill

or on slippery surfaces

when you're driving slower than

35 mph (55 km/h).

Remember that driving in FOUR-WHEEL HIGH (4H)

or FOUR-WHEEL LOW (4L)

may reduce fuel

economy. Also, driving in four-wheel drive on dry

pavement could cause your tires to wear faster and make

your transfer case harder

to shift.

2-19

ProCarManuals.com

Page 130 of 354

Control of a Vehicle

You have three systems that make your vehicle go where

you want it to

go. They are the brakes, the steering and

the accelerator. All three systems have to do their work

at the places where the tires meet the road.

Sometimes, as when you’re driving on snow or ice, it’s

easy to ask more

of those control systems than the tires

and road can provide. That means you can lose control

of your vehicle.

Braking

Braking action involves perception time and reaction

time.

First, you have to decide to push on the brake pedal.

That’s

perception time. Then you have to bring up your

foot and do it. That’s

reaction time.

Average reaction time is about 3/4 of a second. But

that’s only an average. It might be less with one driver

and as long as two or three seconds or more with

another. Age, physical condition, alertness, coordination,

and eyesight all play a part.

So do alcohol, drugs and

frustration. But even in

3/4 of a second, a vehicle

moving at

60 mph (100 km/h) travels 66 feet (20 m).

That could be a lot of distance in an emergency, so

keeping enough space between your vehicle and others

is important.

And,

of course, actual stopping distances vary greatly

with the surface of the road (whether it’s pavement or

gravel); the condition

of the road (wet, dry, icy); tire

tread; and the condition

of your brakes.

4-5

ProCarManuals.com

Page 133 of 354

Braking in Emergencies

At some time, nearly every driver gets into a situation

that requires hard braking.

You have the rear-wheel anti-lock braking system. Your

front wheels can stop rolling when

you brake very hard.

Once they do, the vehicle can’t respond to your steering.

Momentum will carry it in whatever direction it was

headed when the front wheels stopped rolling. That

could be

off the road, into the very thing you were trying

to avoid, or into traffic.

So, use a “squeeze” braking technique. This will give

you maximum braking while maintaining steering

control. You

do this by pushing on the brake pedal with

steadily increasing pressure. When

you do, it will help

maintain steering control.

In many emergencies, steering

can help you more than even the very best braking.

Steering

Power Steering

If you lose power steering assist because the engine

stops or the system is not functioning, you

can steer but

it will take much more effort.

Steering Tips

Driving on Curves

It’s important to take curves at a reasonable speed.

A lot of the “driver lost control” accidents mentioned on

the news happen on curves. Here’s why:

Experienced driver or beginner, each

of us is subject to

the same laws

of physics when driving on curves. The

traction

of the tires against the road surface makes it

possible for the vehicle

to change its path when you turn

the front wheels.

If there’s no traction, inertia will keep

the vehicle going in the same direction.

If you’ve ever

tried

to steer a vehicle on wet ice, you’ll understand this.

The traction you can get in

a curve depends on the

condition of your tires and the road surface, the angle at

which the curve is banked, and your speed. While

you’re

in a curve, speed is the one factor you can

control.

ProCarManuals.com

Page 134 of 354

Suppose you’re steering through a sharp curve.

Then you suddenly apply the brakes. Both control

systems

-- steering and braking -- have to do their

work where the tires meet the road. Adding the hard

bralung can demand too much at those places. You can

lose control.

The same thing can happen if you’re steering through

a

sharp curve and you suddenly accelerate. Those two

control systems

-- steering and acceleration -- can

overwhelm those places where the tires meet the road

and make

you lose control.

What should

you do if this ever happens? Ease up on the

brake or accelerator pedal, steer the vehicle

the way you

want it to go, and slow down.

Speed limit signs near curves warn that

you should

adjust your speed.

Of course, the posted speeds are

based on good weather and road conditions. Under less

favorable conditions you’ll want to go slower.

Steering in Emergencies

There are times when steering can be more effective

than braking. For example,

you come over a hill and

find a truck stopped in your lane,

or a car suddenly pulls

out from nowhere,

or a child darts out from between

parked cars and stops right in front

of you. You can

avoid these problems by braking

-- if you can stop in

time. But sometimes

you can’t; there isn’t room. That’s

the time for evasive action

-- steering around the

problem.

Your Geo can perform very well in emergencies like

these. First apply your brakes, but not enough to lock

your front wheels. (See “Braking in Emergencies’’

earlier in this section.) It is better to remove

as much

speed as you can from a possible collision. Then steer

around the problem,

to the left or right depending on the

space available.

If you need to reduce your speed as you approach

a

curve, do it before you enter the curve, while your front

wheels are straight ahead.

Try

to adjust your speed so you can “drive” through the

curve. Maintain

a reasonable, steady speed. Wait to

accelerate until you are out

of the curve, and then

accelerate gently into the straightaway.

4-9

ProCarManuals.com

Page 137 of 354

Check your mirrors, glance over your shoulder, and

start your left lane change signal before moving out

of the right lane to pass. When you are far enough

ahead

of the passed vehicle to see its front in your

inside mirror, activate your right lane change signal

and move back into the right lane. (Remember that

your right outside mirror is convex. The vehicle

you

just passed may seem to be farther away from you

than it really is.)

Try not to pass more than one vehicle at a time on

two-lane roads. Reconsider before passing the

next

vehicle.

0 Don’t overtake a slowly moving vehicle too rapidly.

Even though the brake lamps are not flashing, it may

be slowing down

or starting to turn.

following driver to get ahead

of you. Perhaps you

can ease a little to the right.

If you’re being passed, make it easy for the

Loss of Control

Let’s review what driving experts say about what

happens when the three control systems (brakes, steering

and acceleration) don’t have enough friction where the

tires meet the road to do what the driver has asked.

In any emergency, don’t give up. Keep trying to steer

and constantly seek an escape route or area

of less

danger.

Skidding

In a skid, a driver can lose control of the vehicle.

Defensive drivers avoid most skids by taking reasonable

care suited to existing conditions, and by not

“overdriving” those conditions. But skids are always

possible.

The three types

of skids correspond to your Geo’s three

control systems. In the braking skid your wheels aren’t

rolling. In the steering or cornering skid, too much speed

or steering in a curve causes tires to slip

and lose

cornering force. And in the acceleration skid too much

throttle causes the driving wheels to spin.

A cornering skid and an acceleration skid are best

handled by easing your foot off the accelerator pedal.

ProCarManuals.com

Page 138 of 354

If your vehicle starts to slide, ease your foot off the

accelerator pedal and quickly steer the way you want the

vehicle to go. If you start steering quickly enough, your

vehicle may straighten

out. Always be ready for a

second skid if it occurs.

Of course, traction is reduced when water, snow, ice,

gravel, or other material is on the road. For safety,

you’ll

want to slow down and adjust your driving to these

conditions. It is important to slow down on slippery

surfaces because stopping distance will be longer and

vehicle control more limited.

While driving

on a surface with reduced traction, try

your best to avoid sudden steering, acceleration, or

braking (including engine braking by shifting to a lower

gear). Any sudden changes could cause the tires to slide.

You may not realize the surface

is slippery until your

vehicle is skidding. Learn

to recognize warning

clues

-- such as enough water, ice or packed snow on

the road to make a “mirrored surface” -- and slow

down when you have any doubt.

Remember: The rear-wheel anti-lock braking system

(RWAL) helps avoid only a rear braking skid.

In a

braking skid (where the front wheels are no longer

rolling), release enough pressure

on the brakes to get the front

wheels rolling again. This restores steering control.

Push the brake pedal down steadily when you have to

stop suddenly. As long as the front wheels are rolling,

you will have steering control.

Driving Guidelines

This multipurpose passenger vehicle is defined as a

utility vehicle

in Consumer Information Regulations

issued by the National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration (NHTSA) of the United States

Department of Transportation, Utility vehicles have

higher ground clearance and a narrower track to make

them capable of performing in a wide variety

of off-road

applications. Specific design characteristics give them

a

higher center of gravity than ordinary cars. An

advantage

of the higher ground clearance is a better

view

of the road allowing you to anticipate problems.

They are

not designed for cornering at the same speeds

as conventional 2-wheel drive vehicles any more than

low-slung sports cars are designed

to perform

satisfactorily under off-road conditions. If at all

possible, avoid sharp turns or abrupt maneuvers.

As with

other vehicles of this type, failure

to operate this vehicle

correctly may result in loss of control or vehicle

rollover.

ProCarManuals.com

Page 140 of 354

Traveling to Remote Areas

You’ll find other important information in this manual.

See “Vehicle Loading,” “Luggage Carrier” and “Tires”

in the Index. It

makes

sense to plan your trip, especially when going

to

a remote area. Know the terrain and plan your route.

You are much less likely to get bad surprises. Get

accurate maps

of trails and terrain. Try to learn of any

blocked or closed roads.

It’s also a good idea to travel with at least one other

vehicle.

If something happens to one of them, the other

can help quickly.

Does your vehicle have

a winch? If so, be sure to read

the winch instructions.

In a remote area, a winch can be

handy

if you get stuck. But you’ll want to know how to

use it properly.

Getting Familiar with Off-Road Driving

It’s a good idea to practice in an area that’s safe and

close to home before you go into the wilderness.

Off-road driving does require some new and different

driving skills. Here’s what we mean.

Tune your senses to different kinds of signals. Your

eyes, for example, need to constantly

sweep the terrain

for unexpected obstacles. Your ears need to listen for

unusual tire or engine sounds. With your anns, hands,

feet, and body you’ll need

to respond to vibrations and

vehicle bounce.

ProCarManuals.com

Page 148 of 354

Driving Across an Incline

Sooner or later, an off-road trail will probably go across

the incline

of a hill. If this happens, you have to decide

whether to try to drive across the incline. Here

are some

things to consider:

0 A hill that can be driven straight up or down may be

too steep to dnve across. When you go straight up or

down a hill, the length of the wheel base (the

distance from the front wheels

to the rear wheels)

reduces the likelihood the vehicle will tumble end

over end. But when you drive across an incline, the

much more narrow track width (the distance between

the left and right wheels) may not prevent the vehicle

from tilting and rolling over. Also, driving across an

incline puts more weight on the downhill wheels.

This could cause a downhill slide or a rollover.

Surface conditions can be a problem when you drive

across a hill. Loose gravel, muddy spots, or even wet

grass can cause your tires to slip sideways, downhill.

If the vehicle slips sideways, it can hit something

that will trip it (a rock, a rut, etc.) and roll over.

0 Hidden obstacles can make the steepness of the

incline even worse. If you drive across a rock with

the uphill wheels, or if the downhill wheels

drop into

a rut or depression, your vehicle can tilt even more.

For reasons like these, you need

to decide carefully

whether to

try to drive across an incline. Just because

the trail goes across the incline doesn’t mean you have

to drive it. The last vehicle to try

it might have rolled

over.

4-23

ProCarManuals.com